When it comes to investing, one of the core skills is being able to accurately assess a company's intrinsic value. After all, a great business isn't much use if you overpay for it. Among the various methods for determining a stock's fair price, discounted cash flow (DCF) is perhaps the most widely discussed. Yet, even Warren Buffett, the epitome of value investing, has admitted that he doesn't rely on DCF in his own approach. So, why is that? To understand this, we need to first get a grasp of what DCF is, how it works, and explore both its strengths and limitations.

Discounted Cash Flow's Definition

Discounted Cash Flow's Definition

Discounted cash flow (DCF) is a financial approach that converts future cash flows into their present value. By applying a discount rate to anticipated future earnings, it provides an estimate of the current fair price of an investment or asset.

It works by estimating a company's future free cash flows and adjusting them to their present value using a discount rate. Essentially, it involves projecting all the cash the business is expected to generate in the future, then applying a discount to reflect their value today. The total of these adjusted cash flows gives an indication of the company's intrinsic value.

At the heart of the Discounted Cash Flow method is the concept that a company’s true value is the sum of the present values of its future free cash flows. This involves three crucial factors: free cash flow, the discount rate, and the terminal value. Together, these elements help investors gauge a company's real worth and decide if the current stock price is reasonable.

Free cash flow refers to the money a company has left after covering operating costs and capital expenditures, which can then be used for dividends, share buybacks, or reinvestment. This cash flow not only highlights the investment needed to maintain and grow the business, but also reflects the company's remaining profitability after sustaining its operations.

The discount rate not only accounts for the time value of money but also reflects the risk associated with the investment. Given factors like inflation and opportunity cost, future cash flows are generally worth less than current ones. As a result, the discount rate is used to adjust these future cash flows to their present value.

In the Discounted Cash Flow method, the discount rate is typically based on the company's Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). WACC takes into account the cost of all the company's capital sources, including both debt and equity, offering investors a comprehensive, risk-adjusted rate for discounting future cash flows.

As it's nearly impossible to accurately predict a company's cash flow for each year far into the future, the DCF method typically focuses on a shorter time horizon, usually between five and ten years. Beyond this forecast period, future cash flows aren't predicted year by year. Instead, a terminal value is calculated to estimate the company's value beyond the forecast period.

This terminal value reflects the present value of expected future cash flows after the forecast period, assuming the company will continue operating at a stable growth rate. This approach simplifies the valuation process while still capturing the long-term value of a company's ongoing operations, providing a comprehensive estimate of its overall worth.

Since it's virtually impossible to predict a company's cash flow with precision over many years, the Discounted Cash Flow method typically focuses on a shorter-term forecast, usually spanning five to ten years. Beyond this period, rather than forecasting year by year, a terminal value is calculated.

This terminal value represents the present value of the company's future cash flows beyond the forecast period, based on the assumption that the company will continue to operate at a steady growth rate. This method streamlines the valuation process, while still capturing the long-term value of the business, offering a more rounded estimate of its overall worth.

The DCF method is also widely used for pricing debt, especially bonds and other fixed-income securities. It involves discounting the future interest payments and principal repayments to their present value, which helps investors determine the bond's market price, as well as its risk and return profile. The discount rate is generally based on prevailing market rates or the investor's required return. If the present value of the discounted cash flows aligns with the bond’s market price, it is considered to be fairly priced; if not, it may be either undervalued or overvalued.

To sum up, the DCF method is a crucial tool for valuation, commonly used to estimate the intrinsic value of stocks or companies. It takes into account the time value of money and risk factors, offering a reliable basis for assessing whether a company is overvalued or undervalued, and ultimately helping investors make more sound decisions.

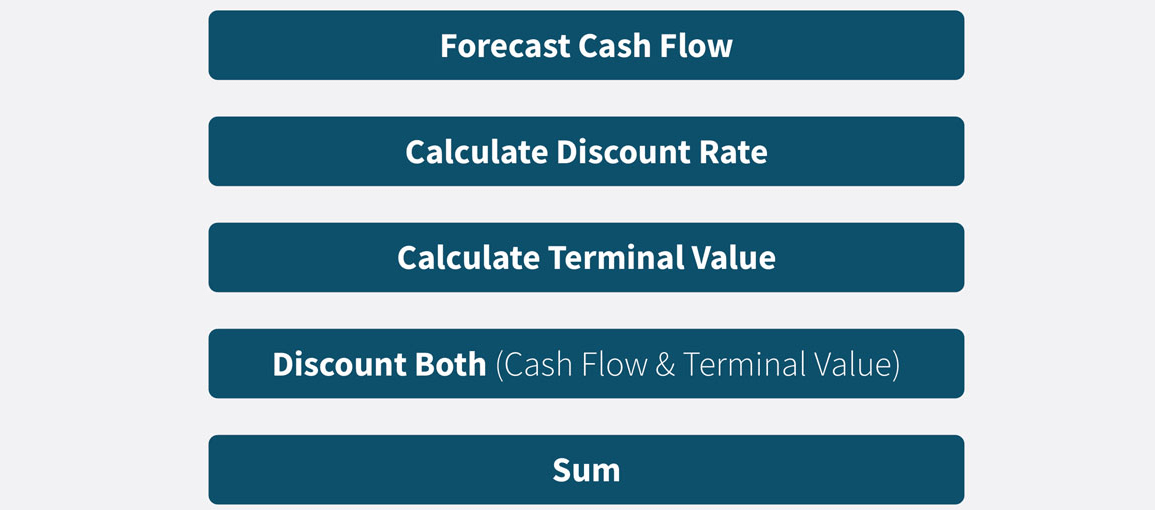

Discounted Cash Flow Valuation Method

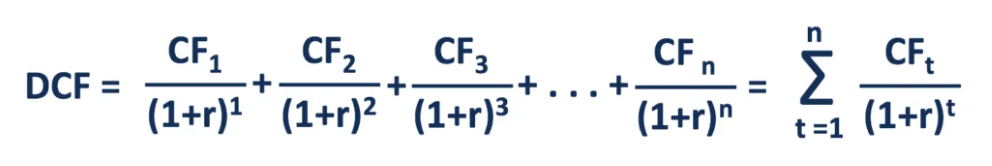

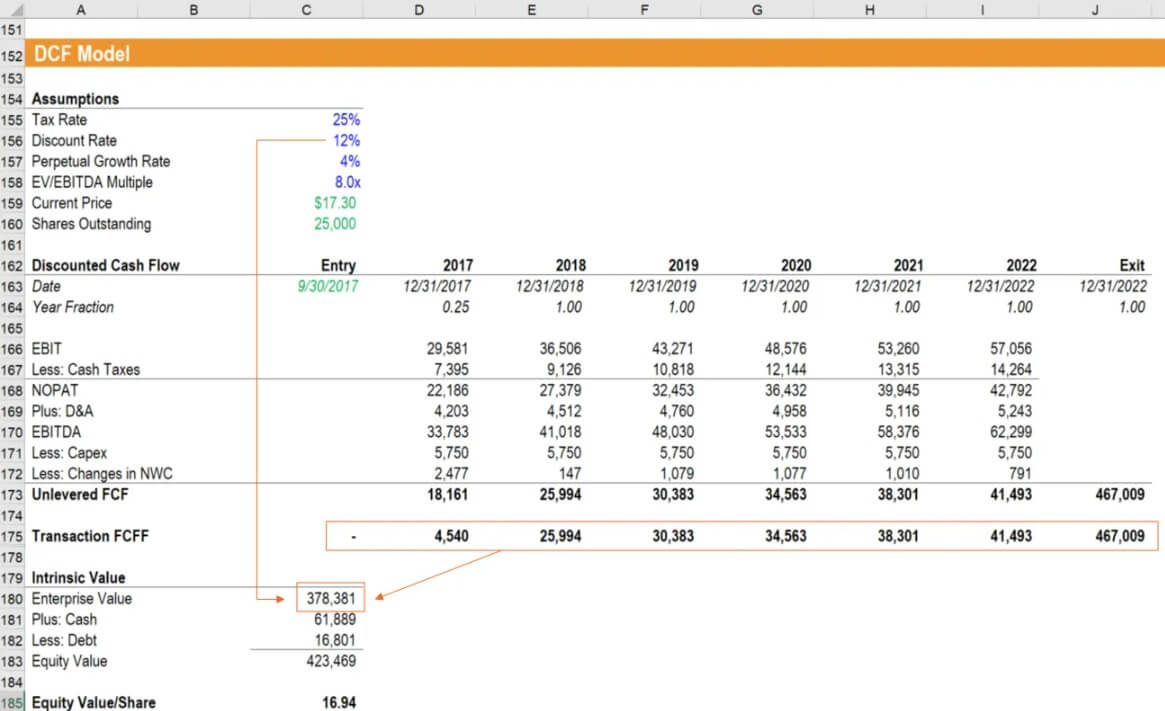

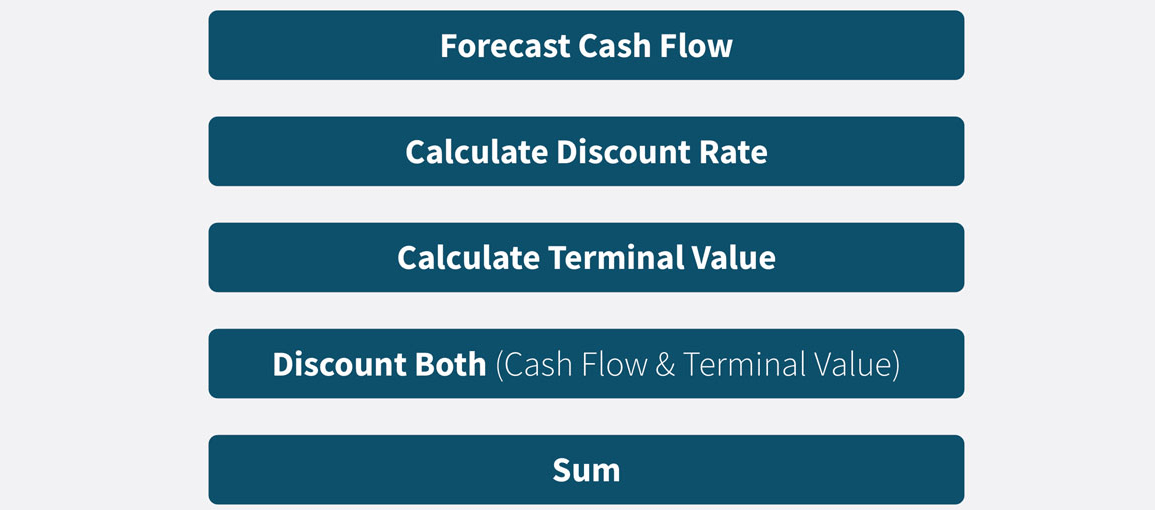

The Discounted Cash Flow method is a way of evaluating the current value of an asset or company by discounting its expected future cash flows to the present. The essence of this approach lies in discounting the company's projected free cash flows (FCF) using an appropriate discount rate, then summing these present values to arrive at the company's total value.

The first step in this process involves forecasting the company's free cash flow over several future periods. Free cash flow refers to the cash available for distribution after accounting for operating expenses and capital expenditures. These projections give investors a clearer picture of the company's future financial performance, enabling more accurate valuation.

The formula for calculating free cash flow is: CF = Operating Profit × (1 - Tax Rate) + Depreciation & Amortisation - Capital Expenditures - ΔWorking Capital

It's important to note that for growth stocks, like those in the tech sector, future cash flows are likely to experience rapid expansion, reflecting their high growth potential. In contrast, value stocks, such as those in consumer goods, typically see more consistent cash flow growth, which mirrors a more stable business model and a mature market environment.

In this method, future cash flows for each year are discounted to their present value. Essentially, the discounting formula transforms each year's forecasted cash flow into its current value using a discount rate, which is usually based on the company's weighted average cost of capital (WACC). The WACC reflects the overall cost of a company’s capital, encompassing both debt and equity financing.

The WACC accounts for the cost of financing, investment opportunities, and the associated risk levels. In times of high interest rates, the WACC tends to increase, which in turn reduces the present value of future cash flows. A higher discount rate lowers the current value of future earnings, thereby affecting the company's overall valuation. As such, accurately calculating the WACC is a crucial step when evaluating a company's value and making sound investment decisions.

The formula for calculating WACC is: WACC = (E/V × Re) + (D/V × Rd × (1 - Tc)), where E is the market value of equity, D is the market value of debt, and V is the total value (equity + debt). Re represents the cost of equity, Rd the cost of debt, and Tc is the corporate tax rate.

Additionally, when considering long-term cash flows, the DCF method needs to factor in the Terminal Value, which represents the total cash flow a company is expected to generate beyond the forecast period. This is typically calculated using a perpetuity growth model (assuming the company's cash flows will continue growing at a steady rate) or an exit multiple approach (which estimates the company's value based on industry-specific multiples). This step ensures that the valuation takes into account the company's potential to generate cash flow in the long run, leading to a more accurate overall valuation.

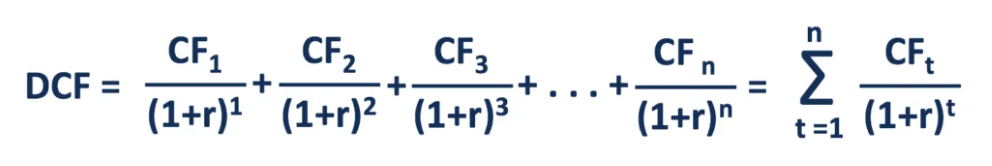

The formula is as follows:

Where: CF t represents the free cash flow in year t, r is the discount rate, t is the year in the forecast period, and n is the number of years in the forecast.

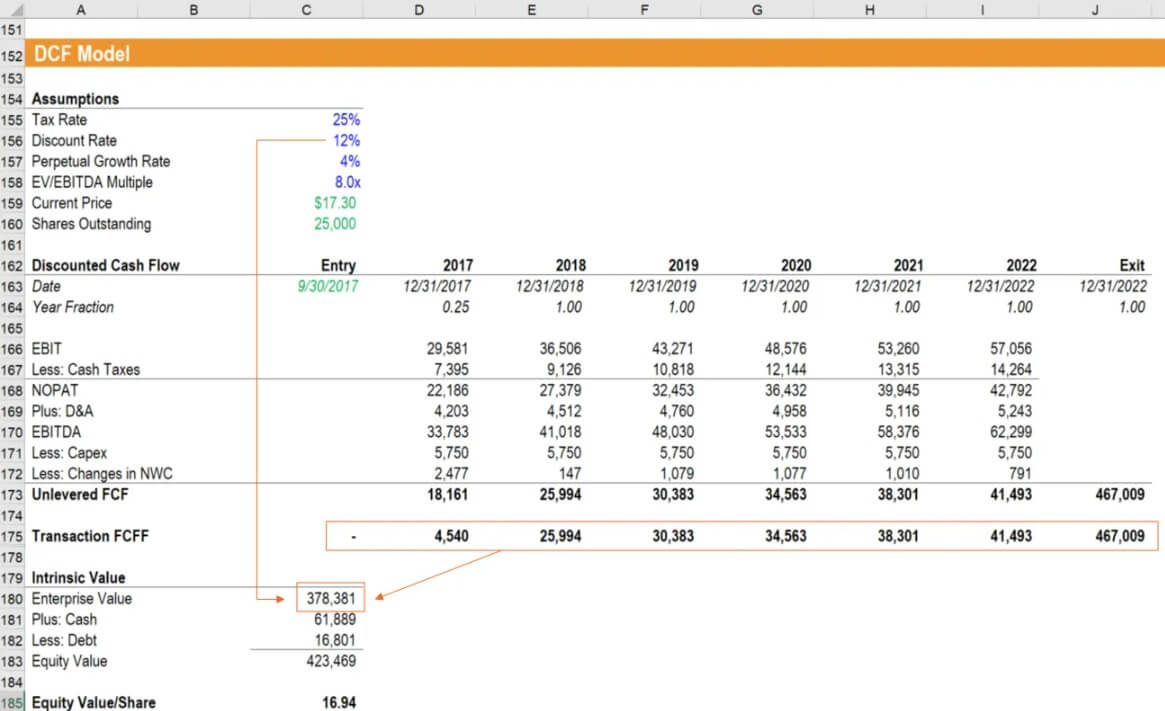

Let's assume you're assessing a company and expect the following free cash flows (CF) over the next five years: Year 1: $1.000.000; Year 2: $1.200.000; Year 3: $1.400.000; Year 4: $1.600.000; Year 5: $1.800.000. The company's weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is 8%, and it's anticipated that the company will continue generating cash flows at a 3% annual growth rate beyond year 5.

By applying an 8% discount rate to each of the future cash flows, the present values come out as follows: Year 1 = $925.926; Year 2 = $1.028.971; Year 3 = $1.112.689; Year 4 = $1.178.930; Year 5 = $1.223.183.

After summing up the discounted cash flows and the terminal value's present value, the company's total valuation would be: $925.926 + $1.028.971 + $1.112.689 + $1.178.930 + $1.223.183 + $25.223.632 ≈ $30.693.331. Therefore, using the DCF method, the estimated intrinsic value of the company is around $30.693.331.

Next, we apply a discount rate (for example, 8%) to each year's free cash flow and the terminal value to bring them back to their present value. This process converts future cash flows and the terminal value into today's value, ensuring we get an accurate estimate of the company's intrinsic worth. After completing these discounting calculations, we arrive at the company's total enterprise value.

The next step is to subtract the company's debts from the enterprise value and add any cash it holds, which gives us the equity value. To find the fair value per share, we divide the equity value by the total number of shares outstanding. This provides investors with a clear idea of the stock's reasonable buy-in price, helping them make more informed decisions.

The discounted cash flow valuation method helps investors assess a company's intrinsic value by forecasting its future cash flows, applying a discount rate, and calculating the terminal value. While it heavily relies on assumptions, it remains a widely-used tool for valuing businesses, particularly those with stable cash flows.

Discounted Cash Flow's Strengths and Weaknesses

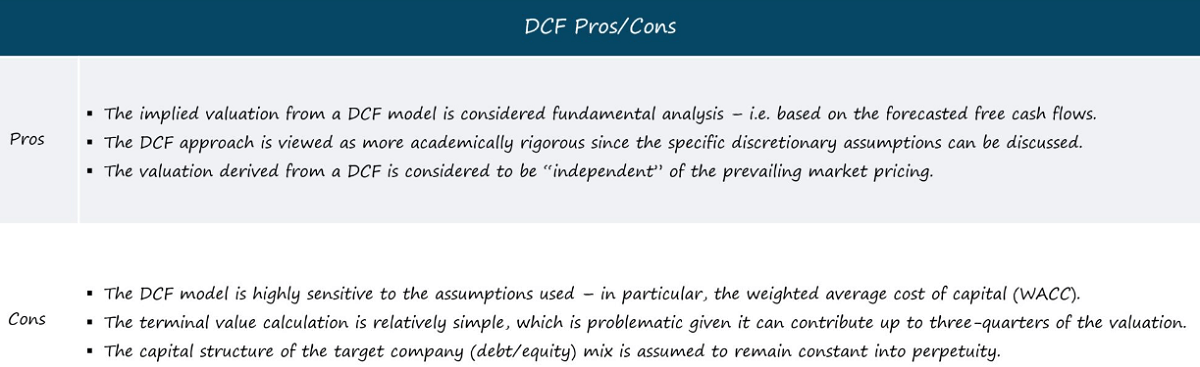

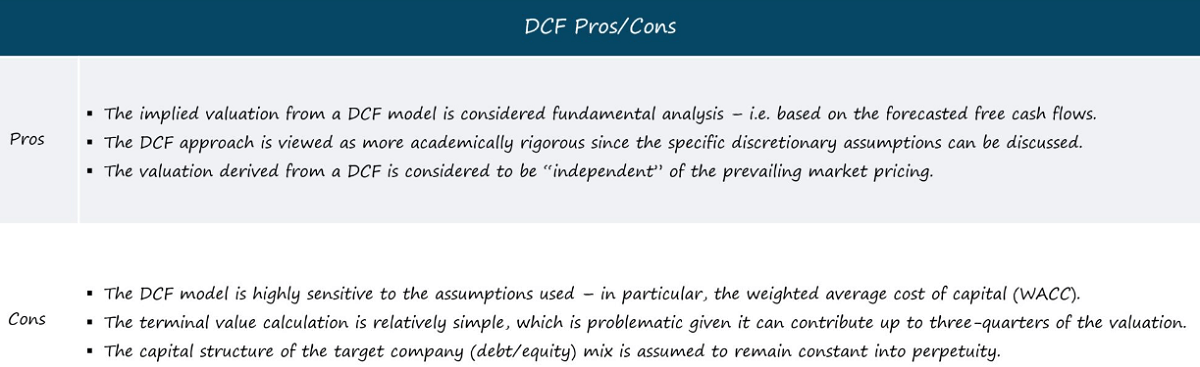

The Discounted Cash Flow method is a popular approach for valuing companies. It works by estimating future cash flows and discounting them back to their present value to determine a company's intrinsic worth. Widely used in investment analysis, particularly among long-term investors, the DCF model offers a thorough understanding of a company's value. However, despite its advantages, it has some limitations, which eventually led Warren Buffett to move away from using it.

One of the key strengths of this method is its solid theoretical grounding. The model is based on the principle of "intrinsic value," which suggests that a company's true value is driven by its future cash flows. This fits closely with the core philosophy of value investing. By forecasting and discounting future cash flows, the DCF method gives a clear view of a company’s actual value. It not only provides insights into the company's long-term earnings potential but also helps investors assess its financial health and growth prospects, allowing for more informed investment choices.

The discounted cash flow method also allows for the discounting of future cash flows to their present value, thereby reflecting the time value of money. This concept highlights the idea that money today is worth more than the same amount in the future, as future cash flows are affected by both time and uncertainty.

By discounting future cash flows, the DCF model provides a grounded approach to valuation, enabling investors to assess the current return on investment more accurately, rather than simply relying on uncertain future profits. This gives investors a clearer picture of the true value of various investments, allowing for more informed comparisons.

Furthermore, the model is highly versatile and can be applied to businesses at any stage of development. By adjusting key assumptions, such as growth rates, discount rates, and terminal values, it can accurately capture a company's intrinsic value. This makes it a powerful tool for valuing companies, particularly those with stable cash flows and established business models.

For established businesses, the DCF model offers a precise valuation by relying on steady cash flow forecasts and a sensible discount rate. For high-growth companies, while predicting future cash flows can be more uncertain, the flexibility of the DCF model gives investors the freedom to adjust their assumptions based on various growth scenarios and market conditions.

By assessing cash flows over a longer period, the model allows investors to take a broader, long-term perspective, moving beyond the noise of short-term market fluctuations and honing in on the company’s sustained earning potential. This is particularly beneficial for those with a long-term investment horizon, as it reduces the noise from short-term market movements when calculating a company’s intrinsic value. By incorporating future cash flows, the DCF model provides a more complete, long-term view of a company’s financial performance, helping investors make more informed, forward-thinking decisions.

Additionally, the DCF model is highly adaptable, allowing investors to fine-tune the growth rates and discount rates according to the specifics of the company. This level of customisation helps ensure that the valuation is based on a detailed understanding of the company and its industry, making it an invaluable tool for investors who want a more precise and realistic assessment of a company’s value. In this way, it can better capture the nuances of a business's performance in particular market environments, helping investors to make more targeted decisions.

When it comes to the drawbacks of the discounted cash flow (DCF) method, the key issue lies in its heavy reliance on future cash flow projections. Given the inherent uncertainty of predicting future cash flows, even slight adjustments to assumptions such as growth rates or discount rates can have a significant impact on the final valuation. This sensitivity means that DCF valuations can be volatile and challenging to get spot-on. As a result, investors need to approach the model's assumptions with caution, considering a range of scenarios to minimise the risk of errors in the forecast.

The discounted cash flow method also presents significant challenges when it comes to valuing emerging or unstable companies. For businesses that are not yet profitable or have highly volatile cash flows – such as startups or rapidly growing tech companies – predicting future cash flows becomes exceptionally difficult. In these cases, the DCF method struggles to offer a reliable valuation, as the inherent uncertainty in cash flow projections means the results could be inaccurate. When a company's financial situation is unstable, DCF is less likely to accurately capture its true market value or the potential risks involved.

Additionally, because the DCF method relies on detailed projections of a company's cash flows over an extended period, it is particularly sensitive to long-term forecasts. However, variables like market conditions, the economic environment, and competitive dynamics can shift significantly over time, and these changes are often difficult to predict with accuracy. The precision of the model hinges on the accuracy of these long-term assumptions, so any errors in forecasting the future can throw the overall valuation off. Even with highly accurate DCF calculations, long-term uncertainties can still cause the valuation to be skewed.

Moreover, the DCF model requires a substantial amount of financial data and assumptions, including forecasts for future cash flows, the determination of the discount rate, and estimates for long-term growth. This makes the DCF model relatively complex and time-consuming, as each assumption and data point has the potential to impact the final valuation.

In comparison, simpler financial metrics, such as the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio or the price-to-book (P/B) ratio, are much easier to calculate and understand. While the DCF method offers in-depth valuation analysis, its complexity and time-intensive nature often lead some investors to favour these more straightforward indicators.

The terminal value calculation is a crucial part of the DCF model, as it encompasses the cash flows expected after the forecast period. However, terminal value is heavily reliant on the assumption of long-term growth rates, which can be difficult to predict accurately. The choice of growth rate has a significant impact on the terminal value, and selecting one that is too high or too low can lead to a valuation that deviates from reality. Therefore, while the terminal value offers an important addition to the company's long-term value, the accuracy and reliability of its calculation are closely tied to the assumptions made about future growth, which means the final valuation can be subject to considerable uncertainty.

In a word, the discounted cash flow method is a powerful tool that can provide investors with valuable insights into a company's intrinsic value. However, its effectiveness hinges on making reasonable assumptions about the future, particularly with regard to cash flows, growth rates, and discount rates. If these assumptions are overly optimistic or overly cautious, the results of the model can be significantly skewed. As such, the DCF method is best suited for experienced investors or analysts, who can use it as a reference tool rather than the sole basis for making investment decisions.

Discounted Cash Flow'sPros and Cons

| Aspect |

Description |

Pros |

Cons |

| Definition |

Converting future cash flows to present value. |

Reflects time value. |

Hard to predict. |

| Cash Flow |

Estimating future free cash flow. |

Reflects future earnings. |

Relies on assumptions. |

| Discount Rate |

Using WACC for discount rate. |

Accounts for capital cost. |

WACC is hard to determine. |

| Terminal Value |

Using growth or exit multiples. |

Reflects long-term potential. |

Assumptions may be inaccurate. |

Disclaimer: This material is for general information purposes only and is not intended as (and should not be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by EBC or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.

Discounted Cash Flow's Definition

Discounted Cash Flow's Definition