White House raged

Last week Fitch Ratings downgraded billions of dollars worth of public

finance credits that are linked to the rating company’s landmark decision to

strip US government debt of its AAA status.

The rating agency cited its outlook that the country’s finances will likely

deteriorate over the next three years given tax cuts, new spending initiatives,

economic shocks and repeated political gridlock.

The White House reacted with anger, sending out a release citing pundits

calling the decision “off-base”, “absurd” and “widely & correctly

ridiculed”.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen called it "entirely unwarranted" because

it ignored improvements in governance metrics during the Biden administration

and the country's economic strength.

The surprising downgrade came two months after the country narrowly averted

default amid political wrangling over the federal borrowing limit.

A wide swathe of assets fell later in the day but the knee-jerk reaction

failed to gain more traction. Similarly, S&P’s rating cut in 2011 triggered

a selloff in risk assets.

Fitch also expects a recession, putting it at odds with the Fed and a growing

proportion of analysts who predict the central bank will succeed in taming

inflation and engineer a soft landing.

Market players stay clam

Jamie Dimon, the chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, said Fitch’s downgrade

shouldn’t be too concerning about how investors view the country’s ability to

pay its debt.

‘It doesn't really matter that much. The markets decide. It's not the rating

agencies,’ he said, adding that the U.S. is home to the ‘best economy the world

ever seen.’

Big holders of US Treasury Securities aren't going to rush to shed their

holdings just because of the downgrade, according to Goldman Sachs.

‘Because Treasury securities are such an important asset class, most

investment mandates and regulatory regimes refer to them specifically, rather

than AAA-rated government debt.’

‘The vast majority of economists and market analysts looking at this are

likely to be equally perplexed by the reasons cited and the timing,’ El-Erian

wrote in a post on Twitter. ‘This announcement is much more likely to be

dismissed than have a lasting disruptive impact on the U.S. economy and

markets.’

‘Treasuries still provide the broad risk off hedge during periods of stress,

which ironically, the downgrade may morph into,’ said Marvin Loh, global macro

strategist at State Street Corp. ‘When we look at 2011, credit and stocks

initially were the most volatile following the S&P downgrade.’

Economists joined a cohort of financial institutions in criticizing Fitch

Ratings’ decision. Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers said while there are

reasons for concern about the long-run trajectory of the US deficit, the

country’s ability to service its debts wasn’t in doubt.

Insoluble debt problem

The U.S. debt burden will reach 118% of GDP by 2025 — more than 2.5 times

higher than the ‘AAA’ median of 39%, according to Fitch, which projects the

debt-to-GDP ratio will rise even further in the longer-term.

The federal deficit hit $1.39 trillion for the first nine months of the

current fiscal year, up some 170% from the same period the year before, partly

due to rising interest rates with the cost of servicing government debt rising

by 25% to an 11-year high of $652 billion.

The U.S. Treasury last week boosted its borrowing forecast for the current

quarter to $1 trillion, well above the $733 billion it had predicted in May. The

country’s fiscal deficit has been growing for years, with little progress over

multiple presidential administrations.

UBS said the underlying conditions that led to Fitch’s decision are worse

than debt ceiling issue that underlays S&P’s similar move more than a decade

ago, citing ‘very large budget deficits.’

The CBO calculates that in the first seven months of the 2023 fiscal year,

underlying government revenues are down 10 per cent with spending up 12 per

cent. This leaves the federal budget deficit more than three times larger than

in the same months of the 2022 fiscal year.

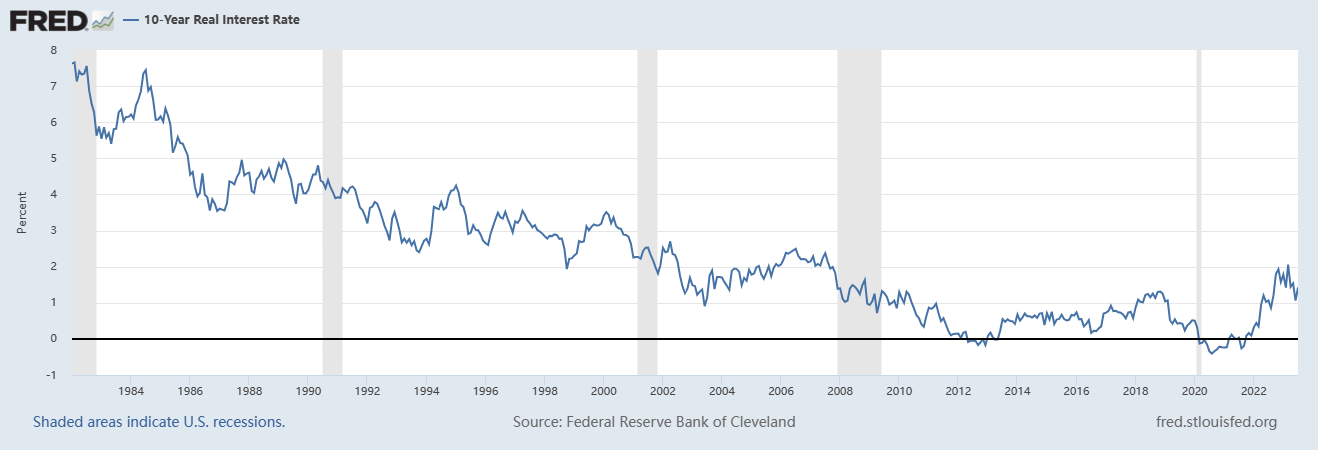

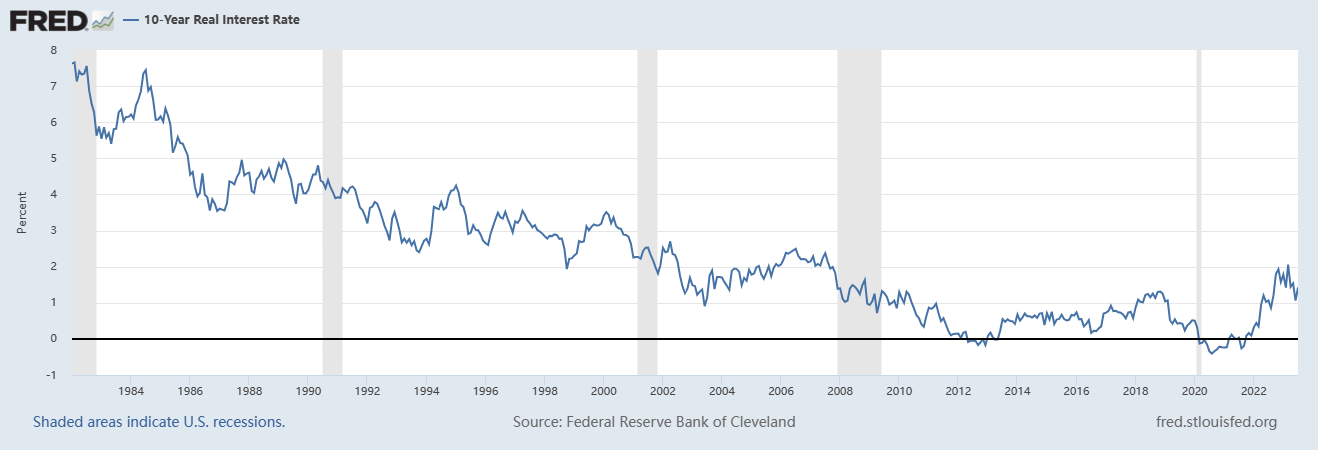

For JPMorgan Chase’s Alexander Wise and Jan Loeys, the ultimate question is

where inflation-adjusted rates eventually go as they maintain a forecast that

the real U.S. 10-year yield will reach 2.5% over the coming decade.

Billionaire investor Bill Ackman said he is betting against 30-year U.S.

Treasurys as a hedge against the impact of long-term rates on stocks.

He argued that if U.S. inflation is 3% in the long term instead of 2%,

30-year Treasury yields could hit 5.5% and it can happen soon.

Interest-only experiment

Economies with the highest credit rating at S&P Global Ratings, Fitch and

Moody’s Investors Service include Germany, Denmark, Netherlands, Sweden and

Norway. That means investors have a limited pool of AAA-rated sovereign debt to

choose from.

While the Treasury securities are still seen as indispensable in a

risk-neutral portfolio, the glut of supply will likely weigh on investors’

appetite for the traditional haven on fears that yields could continue to move

higher.

The dollar’s share of allocated foreign exchange reserves in 2022 Q4 was

58.4%, according to the IMF. The consistent drop in dollar shares over years

have sparked controversy about the dollar’s losing its global dominance.

Most official dollar reserves are invested in Treasury securities, so the dim

prospect for the assets may nudge reserve mangers towards other

dollar-denominated securities or even a further diversification from the

dollar.

The dollar’s narrowing rate advantage over the euro and the BOJ’s potential

policy tweak could give another meaningful impetus to de-dollarization process

if U.S. inflation remains higher than that in Europe and Japan for a prolonged

period.

China, the U.S.’ second-largest creditor, reduced its holdings of U.S.

Treasury bonds in May to the lowest level in 13 years, as foreign investors sold

for the first time in 4 months.

Still it is not a close call. Tuesday’s $42 billion sale of three-year notes

produced a lower-than-expected yield, a sign that demand was stronger than

anticipated.

Borrowing without limit steers the U.S. into unchartered territory

precariously. Ultimately, it will prove to be calamitous to carry on the

interest-only experiment.